How to create arrays with regularly-spaced values#

There are a few NumPy functions that are similar in application, but which provide slightly different results, which may cause confusion if one is not sure when and how to use them. The following guide aims to list these functions and describe their recommended usage.

The functions mentioned here are

1D domains (intervals)#

linspace vs. arange#

Both numpy.linspace and numpy.arange provide ways to partition an interval

(a 1D domain) into equal-length subintervals. These partitions will vary

depending on the chosen starting and ending points, and the step (the length

of the subintervals).

Use

numpy.arangeif you want integer steps.numpy.arangerelies on step size to determine how many elements are in the returned array, which excludes the endpoint. This is determined through thestepargument toarange.Example:

>>> np.arange(0, 10, 2) # np.arange(start, stop, step) array([0, 2, 4, 6, 8])

The arguments

startandstopshould be integer or real, but not complex numbers.numpy.arangeis similar to the Python built-inrange.Floating-point inaccuracies can make

arangeresults with floating-point numbers confusing. In this case, you should usenumpy.linspaceinstead.Use

numpy.linspaceif you want the endpoint to be included in the result, or if you are using a non-integer step size.numpy.linspacecan include the endpoint and determines step size from the num argument, which specifies the number of elements in the returned array.The inclusion of the endpoint is determined by an optional boolean argument

endpoint, which defaults toTrue. Note that selectingendpoint=Falsewill change the step size computation, and the subsequent output for the function.Example:

>>> np.linspace(0.1, 0.2, num=5) # np.linspace(start, stop, num) array([0.1 , 0.125, 0.15 , 0.175, 0.2 ]) >>> np.linspace(0.1, 0.2, num=5, endpoint=False) array([0.1, 0.12, 0.14, 0.16, 0.18])

numpy.linspacecan also be used with complex arguments:>>> np.linspace(1+1.j, 4, 5, dtype=np.complex64) array([1. +1.j , 1.75+0.75j, 2.5 +0.5j , 3.25+0.25j, 4. +0.j ], dtype=complex64)

Other examples#

Unexpected results may happen if floating point values are used as

stepinnumpy.arange. To avoid this, make sure all floating point conversion happens after the computation of results. For example, replace>>> list(np.arange(0.1,0.4,0.1).round(1)) [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4] # endpoint should not be included!

with

>>> list(np.arange(1, 4, 1) / 10.0) [0.1, 0.2, 0.3] # expected result

Note that

>>> np.arange(0, 1.12, 0.04) array([0. , 0.04, 0.08, 0.12, 0.16, 0.2 , 0.24, 0.28, 0.32, 0.36, 0.4 , 0.44, 0.48, 0.52, 0.56, 0.6 , 0.64, 0.68, 0.72, 0.76, 0.8 , 0.84, 0.88, 0.92, 0.96, 1. , 1.04, 1.08, 1.12])

and

>>> np.arange(0, 1.08, 0.04) array([0. , 0.04, 0.08, 0.12, 0.16, 0.2 , 0.24, 0.28, 0.32, 0.36, 0.4 , 0.44, 0.48, 0.52, 0.56, 0.6 , 0.64, 0.68, 0.72, 0.76, 0.8 , 0.84, 0.88, 0.92, 0.96, 1. , 1.04])

These differ because of numeric noise. When using floating point values, it is possible that

0 + 0.04 * 28 < 1.12, and so1.12is in the interval. In fact, this is exactly the case:>>> 1.12/0.04 28.000000000000004

But

0 + 0.04 * 27 >= 1.08so that 1.08 is excluded:>>> 1.08/0.04 27.0

Alternatively, you could use

np.arange(0, 28)*0.04which would always give you precise control of the end point since it is integral:>>> np.arange(0, 28)*0.04 array([0. , 0.04, 0.08, 0.12, 0.16, 0.2 , 0.24, 0.28, 0.32, 0.36, 0.4 , 0.44, 0.48, 0.52, 0.56, 0.6 , 0.64, 0.68, 0.72, 0.76, 0.8 , 0.84, 0.88, 0.92, 0.96, 1. , 1.04, 1.08])

geomspace and logspace#

numpy.geomspace is similar to numpy.linspace, but with numbers spaced

evenly on a log scale (a geometric progression). The endpoint is included in the

result.

Example:

>>> np.geomspace(2, 3, num=5)

array([2. , 2.21336384, 2.44948974, 2.71080601, 3. ])

numpy.logspace is similar to numpy.geomspace, but with the start and end

points specified as logarithms (with base 10 as default):

>>> np.logspace(2, 3, num=5)

array([ 100. , 177.827941 , 316.22776602, 562.34132519, 1000. ])

In linear space, the sequence starts at base ** start (base to the power

of start) and ends with base ** stop:

>>> np.logspace(2, 3, num=5, base=2)

array([4. , 4.75682846, 5.65685425, 6.72717132, 8. ])

nD domains#

nD domains can be partitioned into grids. This can be done using one of the following functions.

meshgrid#

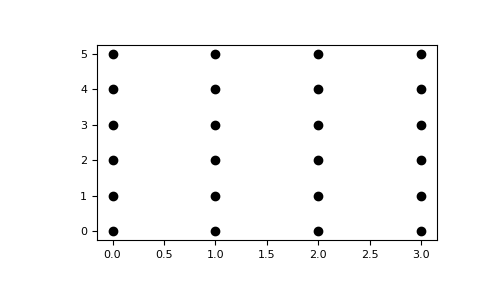

The purpose of numpy.meshgrid is to create a rectangular grid out of a set

of one-dimensional coordinate arrays.

Given arrays

>>> x = np.array([0, 1, 2, 3]) >>> y = np.array([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

meshgrid will create two coordinate arrays, which can be used to generate

the coordinate pairs determining this grid.

>>> xx, yy = np.meshgrid(x, y) >>> xx array([[0, 1, 2, 3], [0, 1, 2, 3], [0, 1, 2, 3], [0, 1, 2, 3], [0, 1, 2, 3], [0, 1, 2, 3]]) >>> yy array([[0, 0, 0, 0], [1, 1, 1, 1], [2, 2, 2, 2], [3, 3, 3, 3], [4, 4, 4, 4], [5, 5, 5, 5]]) >>> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt >>> plt.plot(xx, yy, marker='.', color='k', linestyle='none')

mgrid#

numpy.mgrid can be used as a shortcut for creating meshgrids. It is not a

function, but when indexed, returns a multidimensional meshgrid.

>>> xx, yy = np.meshgrid(np.array([0, 1, 2, 3]), np.array([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]))

>>> xx.T, yy.T

(array([[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2],

[3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3]]),

array([[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]]))

>>> np.mgrid[0:4, 0:6]

array([[[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2],

[3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3]],

[[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]]])

ogrid#

Similar to numpy.mgrid, numpy.ogrid returns an open multidimensional

meshgrid. This means that when it is indexed, only one dimension of each

returned array is greater than 1. This avoids repeating the data and thus saves

memory, which is often desirable.

These sparse coordinate grids are intended to be use with Broadcasting. When all coordinates are used in an expression, broadcasting still leads to a fully-dimensonal result array.

>>> np.ogrid[0:4, 0:6]

[array([[0],

[1],

[2],

[3]]), array([[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]])]

All three methods described here can be used to evaluate function values on a grid.

>>> g = np.ogrid[0:4, 0:6]

>>> zg = np.sqrt(g[0]**2 + g[1]**2)

>>> g[0].shape, g[1].shape, zg.shape

((4, 1), (1, 6), (4, 6))

>>> m = np.mgrid[0:4, 0:6]

>>> zm = np.sqrt(m[0]**2 + m[1]**2)

>>> np.array_equal(zm, zg)

True